Blog

Feb 3, 2026

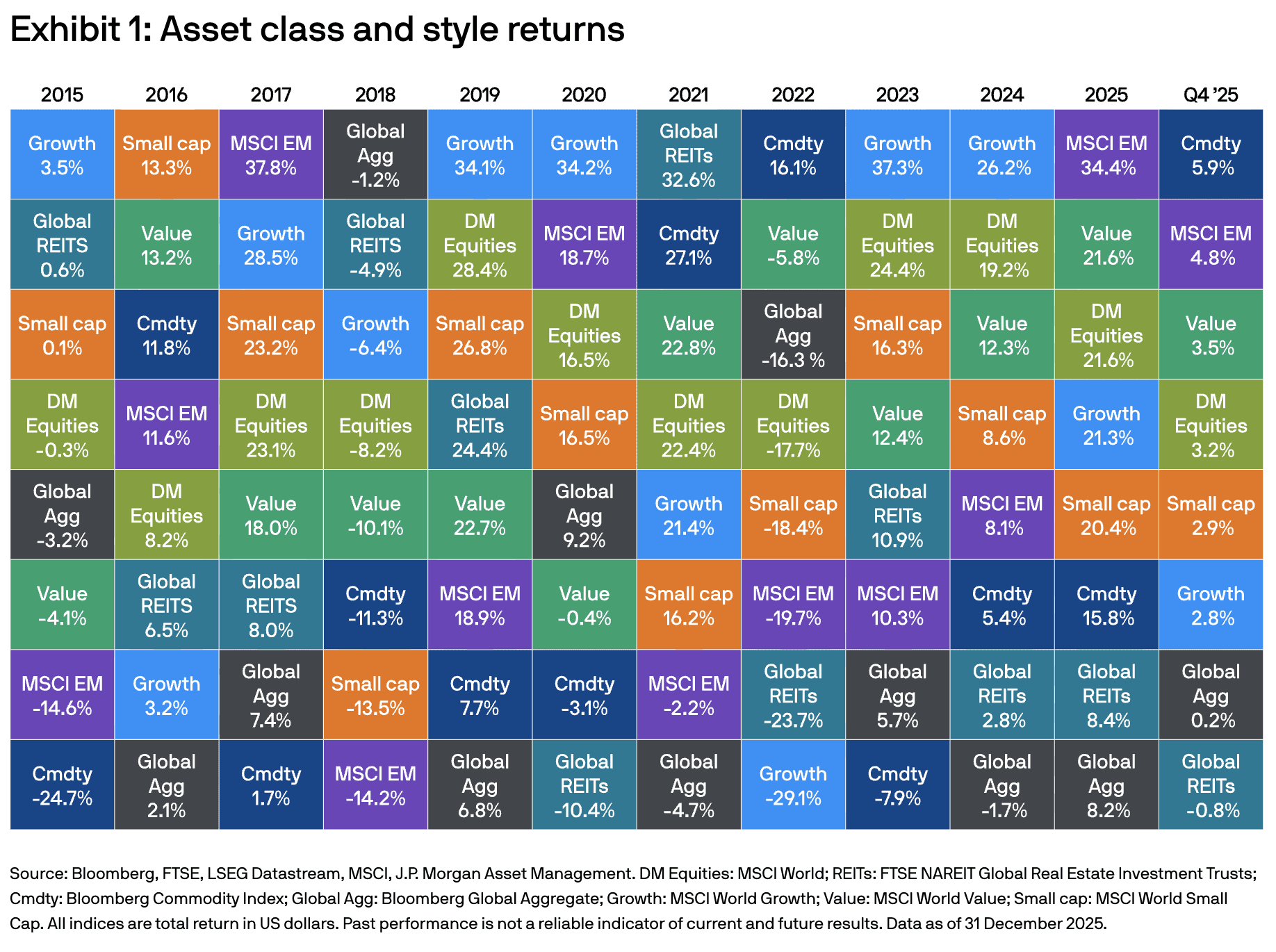

For the first time in over a decade, cash feels competitive. Money market funds yielded an average 5.27% in late 2024, while high-yield savings accounts hovered near 5% APY. Meanwhile, the S&P 500 delivered total returns exceeding 25% that same year—yet many clients saw their portfolios swing violently between gains and losses.

So when a 62-year-old pre-retiree asks whether it makes sense to hold 40% in cash "just for a year or two," the question isn't naive. It's rational. And answering it well requires more than reciting historical equity premiums.

Why This Time Feels Different

Cash hasn't been a legitimate opportunity cost since 2007. For 15 years, money market funds paid functionally zero while inflation averaged 2.3% annually. The Federal Reserve's aggressive rate hikes pushed the federal funds rate to 5.33%—the highest level since 2001.

Suddenly, "cash drag" became "cash strategy." But real yields tell only part of the story. What matters isn't whether cash pays 5% today—it's whether that return compensates for missing periods when equities reprice meaningfully.

The Opportunity Cost That Compounds Silently

Consider two scenarios with a $1 million portfolio:

Scenario A: 60% equity, 40% cash at 5%

After 12 months: $1.14 million

After 5 years (assuming cash drops to 3%): $1.52 million

Scenario B: Traditional 60/40 stock-bond mix

After 12 months: $1.132 million

After 5 years (equities at 10.5% historical average): $1.66 million

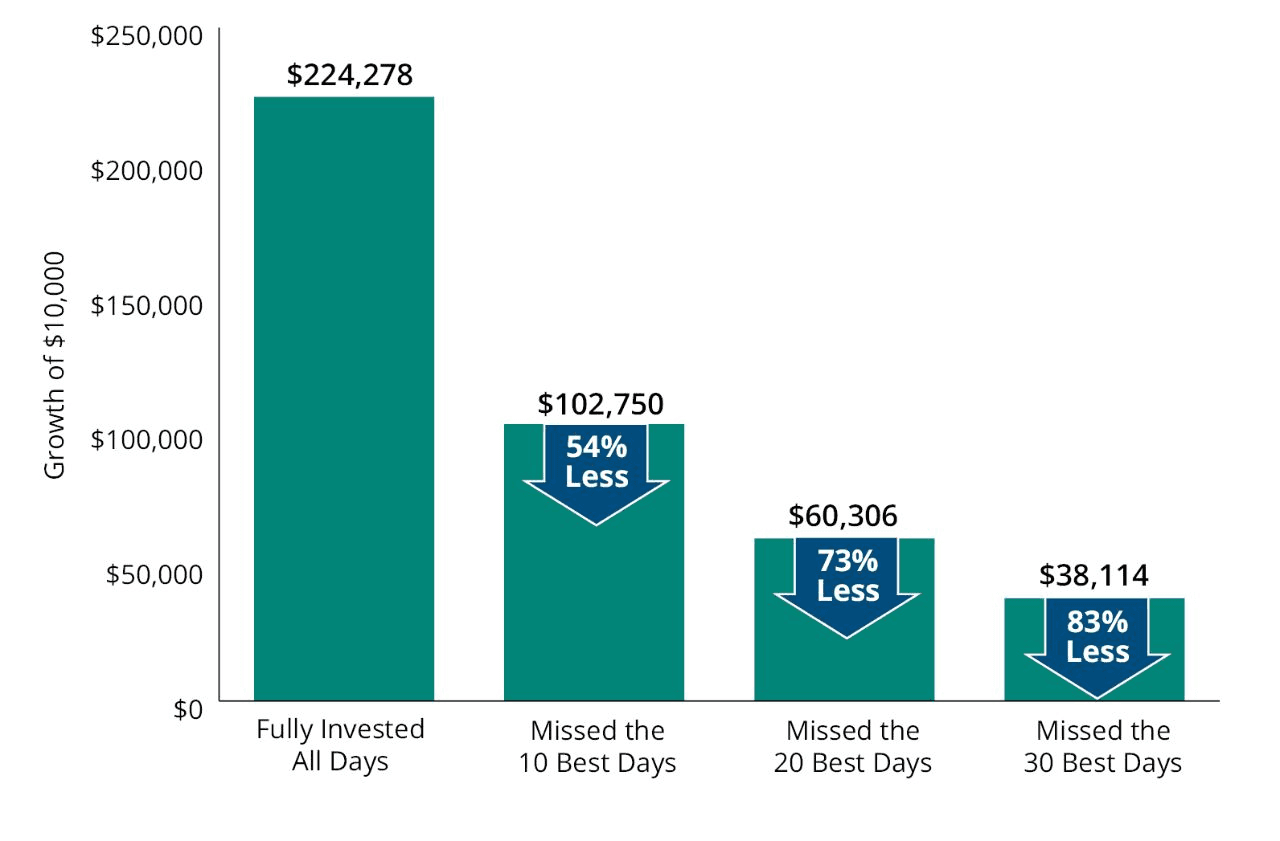

The gap—over $140,000—isn't explained by a single year of underperformance. It's the mathematical consequence of missing reinvestment during recovery periods. Research from Vanguard demonstrates that 70% of equity returns occur during the 10 best days of any given decade—and those days are impossible to predict.

Sequence-of-Returns Risk Cuts Both Ways

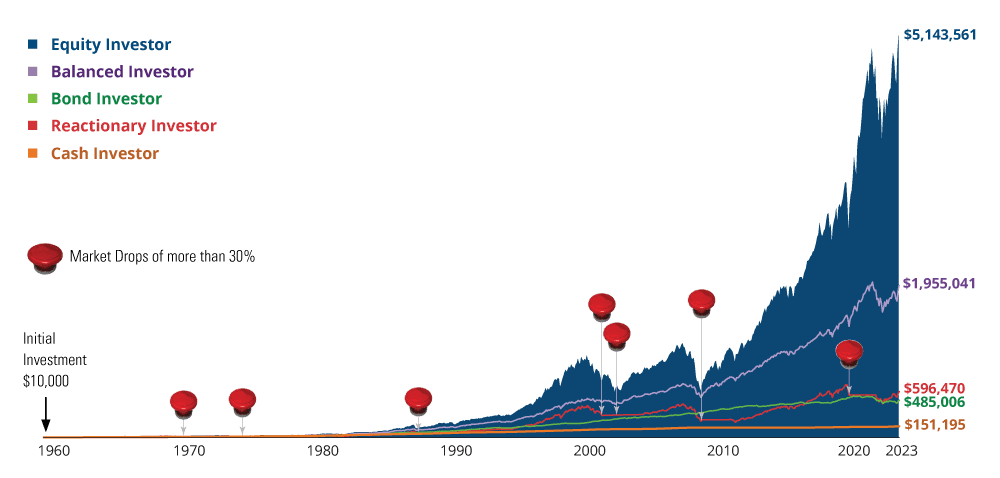

For retirees, the calculus becomes more urgent. Sequence-of-returns risk is well documented—withdrawing from portfolios during early years of poor performance creates catastrophic outcomes. Holding 24–36 months of spending needs in liquid reserves allows retirees to avoid selling equities into losses.

But the inverse risk is equally real and less discussed:

A client retiring in 2010 with 40% cash missed the 470% cumulative return the S&P 500 delivered over the subsequent decade

That shortfall compounds across every future withdrawal

The difference between prudent liquidity management and structural underexposure is often just 12–18 months

Advisors who treat cash tactically—maintaining fixed reserves while systematically rebalancing equity exposure—mitigate both forms of sequence risk.

Inflation Expectations Matter More Than Rates

Current yields don't exist in isolation. The Federal Reserve's Summary of Economic Projections forecasted inflation settling near 2.3% through 2025. If cash yields decline to 3.5% as the Fed continues easing, real returns compress to 1.5% or less.

The asymmetry is critical:

Cash yields can only fall from current levels

Equity returns are bounded by neither current rates nor recent volatility

A client locking in 5% today may feel vindicated during a 10% correction—but devastated after missing a 30% recovery while earning 3%

This isn't about forecasting market direction. It's recognizing that cash offers protection during drawdowns while introducing irreversible opportunity cost during expansions.

The Behavioral Trap: Feeling Smart vs. Being Right

When equities experience routine volatility—a 7% pullback, a two-month consolidation—cash holders feel validated. But this misattributes skill to luck.

The reality:

Volatility is not loss for clients with long time horizons

Research from Dalbar shows individual investors underperform market returns by 3–4% annually

Primary driver: poor timing decisions—buying after rallies, selling during corrections, holding cash while waiting for "clarity"

The fiduciary responsibility isn't to make clients feel comfortable in the moment. It's to construct portfolios that maximize risk-adjusted returns across their investment horizon.

Rebalancing as a Systematic Hedge

The counterargument to elevated cash isn't "always be 100% invested." It's that liquidity should serve a structural purpose, not a tactical one.

A well-designed approach:

Maintains cash allocations tied to specific needs: emergency reserves, planned withdrawals, near-term liabilities

Uses excess liquidity as a rebalancing reserve—deployed systematically when allocations drift below policy targets

Captures both downside protection and upside participation

The 2024 BlackRock Global Outlook emphasized that disciplined rebalancing contributed 0.4%–0.8% annually to long-term portfolio returns—not by timing the market, but by enforcing contrarian positioning through rules, not emotion.

When Cash Makes Sense—and When It Doesn't

Legitimate scenarios for elevated cash:

Near-term liquidity needs (home purchase, tuition funding within 18 months)

Behavioral risk mitigation for clients with documented panic-selling history

Defined short-term liabilities (24–36 months of retirement income reserves)

Where cash becomes problematic:

Held as a market timing position—waiting for "better entry points"

Preserving optionality indefinitely

Avoiding the discomfort of volatility

Cash is not a neutral position. It's an active bet that the opportunity cost of non-investment will be offset by future repricing—a bet most investors lose.

The Infrastructure That Enforces Discipline

Legacy platforms make systematic rebalancing cumbersome—requiring manual intervention, batch processing, and trade-by-trade execution. The operational friction alone discourages frequent rebalancing, allowing cash positions to drift into unintentional allocations.

Purpose-built infrastructure automates policy enforcement:

When equities dip below threshold, cash reserves deploy automatically

When risk assets appreciate beyond targets, gains are systematically harvested

The process removes emotion and ensures cash serves its intended function

The distinction between platforms that enable this discipline and those requiring manual override compounds across thousands of rebalancing events.

What the Math Actually Says

The question isn't whether cash paying 5% is attractive—it is. The question is whether that yield compensates for the structural risks elevated cash allocations introduce: opportunity cost during recoveries, reverse sequence risk for retirees, behavioral reinforcement of market timing, and erosion of systematic rebalancing discipline.

For most clients with time horizons beyond three years, the answer is no. Cash should remain a functional allocation tied to specific liquidity needs and rebalancing reserves—not a comfort position or a timing tool.

Advisors who construct portfolios around rules rather than forecasts—maintaining policy allocations through systematic rebalancing, defining cash reserves based on client-specific liabilities, and leveraging infrastructure that enforces discipline—deliver better long-term outcomes.

Not because they predict market direction, but because they avoid the compounding cost of inaction.

Related

Get Started

Experience the full power of our SaaS platform with a risk-free trial. Join countless businesses who have already transformed their operations. No credit card required.

FAQs